OFF THE WIRE

By Simon Davis-Cohen

Cops are using roadside traffic stops to throw the Fourth Amendment out the window.

Checkpoints occupy a unique position in the American justice system.

At these roadside stations, where police question drivers in search of

the inebriated or “illegal," anyone can be stopped and questioned,

regardless of probable cause, violating the Fourth Amendment’s

protection against “general warrants” that do not specify the

who/what/where/why of a search or seizure. Though the Supreme Court

agrees that checkpoints skirt the Fourth Amendment, the Court has been

clear that the “special needs” checkpoints serve, like traffic safety

and immigration enforcement, trump the “slight” intrusions on motorists’

rights.

We have checkpoints for bicycle safety, gathering witnesses, drug

trafficking, “illegal” immigration and traffic safety. Many states, like California,

require cops to abide by “neutral” mathematical formulas when choosing

which drivers to pull over (like 1 in every 10 cars). In reality, these

decisions are left to the discretion of individual police officers,

which results in a type of vehicular stop and frisk.

That’s why people in Arizona have sued

the Department of Homeland Security for its wanton deployment of

immigration checkpoints in their state. Among their complaints are

racial profiling, harassment, assault and unwarranted interrogation, and

detention not related to the express “special need” of determining

peoples’ immigration status.

A key legal detail about checkpoints is that they cannot be used for

crime control, as that would require individualized probable cause. But

legal scholars argue

that non-criminally-minded checkpoints are also illegal. They point out

that the Fourth Amendment protected the colonists from being searched

for non-criminal “wrongdoing.” Doing nothing wrong at all, they

argue, is not grounds to be searched or have your property seized.

Regardless, unlike DUI checkpoints, these immigration checkpoints, expanded by the 2006 Secure Fence Act, are only allowed within 100 miles of the continental United States’ border. But that’s a big perimeter.

Nine of the country’s 10 largest cities, entire states and some two

thirds of the US population reside within this constitutionally exempt

zone.

At these checkpoints—some of which have become permanent

fixtures on the highway—people are forced to stop when flagged down,

again regardless of probable cause. But the extent to which people are

legally obliged to answer officers’ questions is unclear and seemingly arbitrary. Not surprisingly, the military's immigration checkpoints have garnered outspoken criticism from across the political spectrum. Legalized by the Supreme Court in 1976, these checkpoints seem to have taken on a new momentum in the post-9/11 era. (Private militias have even taken to setting up their own versions.)

DUI checkpoints, on the other hand, deemed constitutional in 1990, monitor roadways in 38 states. But they have been outlawed by 12 others that have invoked states’ rights to increase federal civil liberty protections. In the Court’s 1990 opinion,

Chief Justice William Rehnquist wrote that states’ interest in

eradicating drunk driving is undisputable and that this “interest”

outweighed “the measure of the intrusion on motorists stopped briefly at

sobriety checkpoints,” which he described as “slight.”

In the dissent, William Brennan reminded the Court that, “some level

of individualized suspicion is a core component of the protection the

Fourth Amendment provides against arbitrary government action.” In

pulling people over at random, checkpoints remove this individualized

component.

Today, the practice seems to be experiencing a renaissance of sorts.

With the help of local police, private government contractors have used

the tactic to collect anonymous breath, saliva and blood ( DNA) samples of American motorists for the federally funded National Roadside Survey of Alcohol and Drugged Driving.

Participation in the survey is voluntary, despite the confusion that

may come with uniformed police asking for bodily fluids. Motorists are

offered $10 for cheek swabs and $50 for blood samples. These practices

have sparked considerable public outrage; law enforcement officials in St. Louis, Missouri and Fort Worth, Texas have stated their intent to limit their future participation in the study.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

Bill & Annie

Art Hall & Rusty

NUFF SAID.......

OOHRAH

ONCE A MARINE,ALWAYS A MARINE

GIVING BACK

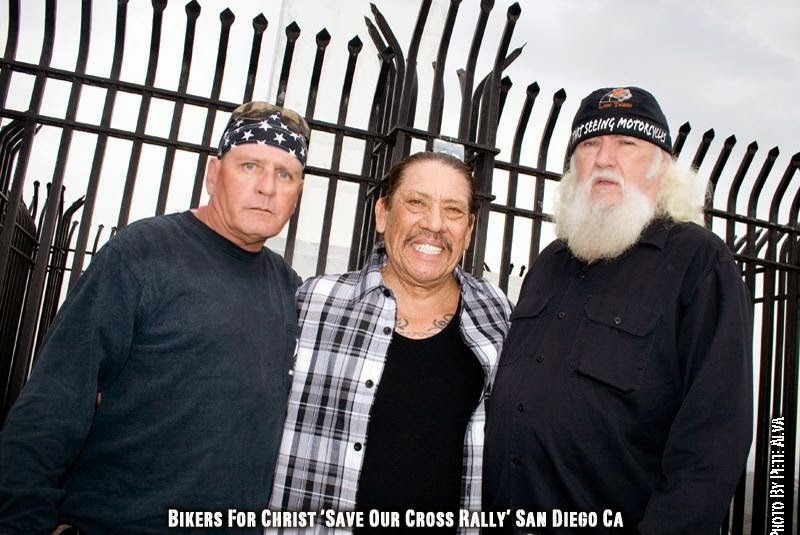

MOUNT SOLEDAD

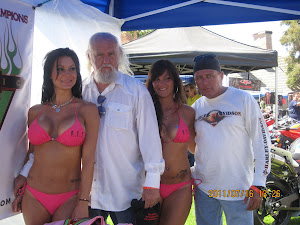

BIKINI BIKE WASH AT SWEETWATER

FRIENDS

BILL,WILLIE G, PHILIP

GOOD FRIENDS

hanging out

brothers

GOOD FRIENDS

Good Friends

Hanging Out

Bill & Annie

Art Hall & Rusty

Art Hall & Rusty

NUFF SAID.......

NUFF SAID......

Mount Soledad

BALBOA NAVAL HOSPITAL

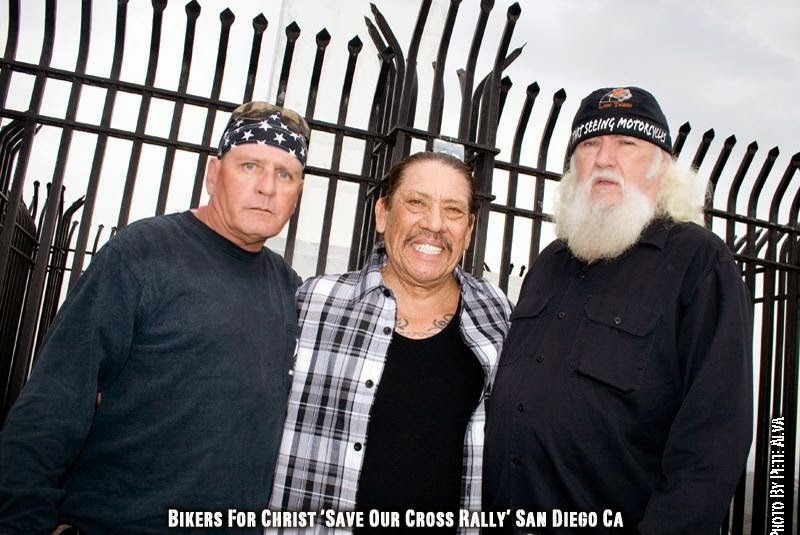

RUSTY DANNY

ANNIE KO PHILIP

PHILIP & ANNIE

OUT & ABOUT

OOHRAH...

OOHRAH

ONCE A MARINE,ALWAYS A MARINE

ONCE A MARINE,ALWAYS A MARINE

American Soldier Network GIVING BACK

GIVING BACK

CATHY & BILL

PHILIP & DANNY & BILL

MOUNT SOLEDAD

bills today

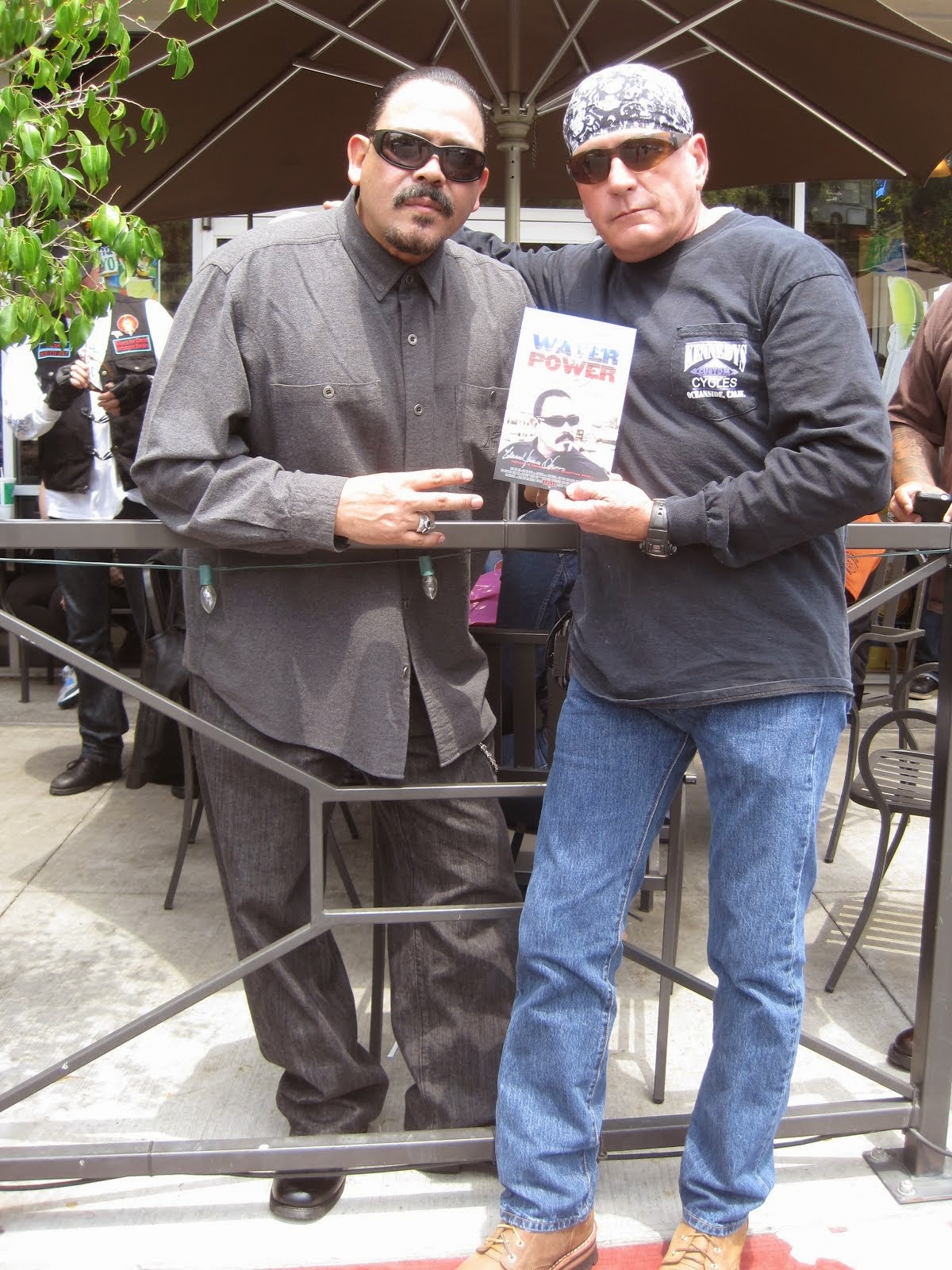

EMILIO & PHILIP

WATER & POWER

WATER & POWER

bootride2013

BIKINI BIKE WASH AT SWEETWATER

ILLUSION OPEN HOUSE

FRIENDS

GOOD FRIENDS

BILL,WILLIE G, PHILIP

GOOD FRIENDS

GOOD FRIENDS

Friends

- http://www.ehlinelaw.com/losangeles-motorcycleaccidentattorneys/

- Scotty westcoast-tbars.com

- Ashby C. Sorensen

- americansoldiernetwork.org

- blogtalkradio.com/hermis-live

- davidlabrava.com

- emiliorivera.com/

- http://kandymankustompaint.com

- http://pipelinept.com/

- http://womenmotorcyclist.com

- http://www.ehlinelaw.com

- https://ammo.com/

- SAN DIEGO CUSTOMS

- www.biggshd.com

- www.bighousecrew.net

- www.bikersinformationguide.com

- www.boltofca.org

- www.boltusa.org

- www.espinozasleather.com

- www.illusionmotorcycles.com

- www.kennedyscollateral.com

- www.kennedyscustomcycles.com

- www.listerinsurance.com

- www.sweetwaterharley.com

Hanging out

hanging out

Good Friends

brothers

GOOD FRIENDS

EMILIO & SCREWDRIVER

GOOD FRIENDS

Danny Trejo & Screwdriver

Good Friends

Navigation

Welcome to Bikers of America, Know Your Rights!

“THE BIKERS OF AMERICA, THE PHIL and BILL SHOW”,

A HARDCORE BIKER RIGHTS SHOW THAT HITS LIKE A BORED AND STROKED BIG TWIN!

ON LIVE TUESDAY'S & THURDAY'S AT 6 PM P.S.T.

9 PM E.S.T.

CATCH LIVE AND ARCHIVED SHOWS

FREE OF CHARGE AT...

BlogTalkRadio.com/BikersOfAmerica.

Two ways to listen on Tuesday & Thursday

1. Call in number - (347) 826-7753 ...

Listen live right from your phone!

2. Stream us live on your computer: http://www.blogtalkradio.com/bikersofamerica.

A HARDCORE BIKER RIGHTS SHOW THAT HITS LIKE A BORED AND STROKED BIG TWIN!

ON LIVE TUESDAY'S & THURDAY'S AT 6 PM P.S.T.

9 PM E.S.T.

CATCH LIVE AND ARCHIVED SHOWS

FREE OF CHARGE AT...

BlogTalkRadio.com/BikersOfAmerica.

Two ways to listen on Tuesday & Thursday

1. Call in number - (347) 826-7753 ...

Listen live right from your phone!

2. Stream us live on your computer: http://www.blogtalkradio.com/bikersofamerica.

Good Times

Hanging Out

Key Words

- about (3)

- contact (1)

- TENNESSEE AND THUNDER ON THE MOUNTAIN (1)

- thinking (1)

- upcoming shows (2)

Blog Archive

-

▼

2019

(367)

-

▼

November

(112)

- BABE OF THE DAY

- This Man Took Over 1,000 Children Of Fallen Soldie...

- BABE OF THE DAY

- BABE OF THE DAY

- BABE OF THE DAY

- BABE OF THE WEEK - CHICA

- 2nd Annual Temecula Toy Run

- Orange County,Ca Deputies fired in evidence audit

- BABE OF THE DAY

- The Worlds First Marijuana Mall Opened in Colorado

- BABE OF THE DAY

- Legalizing Marijuana Nationwide Would Create One M...

- GOP lawmaker wants members of Congress to be drug ...

- BABE OF THE DAY

- Czech government tells its citizens how to fight t...

- POLICE DEVIANCE & ETHICS

- BABE OF THE DAY

- Dear Americans: This Law Makes It Possible To Arre...

- WHAT IS R.I.C.O.?

- 10 Painfully True Examples of Murphy’s Laws for Mo...

- Free the Nipple' movement: Women can now legally g...

- Statistics Prove Outlaw Motorcycle Clubs Not A Pub...

- 2019 National Gang Threat Assessment – Emerging Tr...

- WISDOM...........

- USA - Does cellphone-sweeping ‘StingRay’ technolog...

- Landmark State Court Ruling Says THC in Blood is N...

- BABE OF THE DAY - How'd you like to come home to ...

- California - Forfeiture Games

- California Public Records Act.

- Meet the machines that steal your phone’s data

- January’s new military shopping benefit delayed fo...

- USA - The Myth of the Rule of Law by John Hasnas

- The Loophole That Lets Cops Stop, Question and Sea...

- BABE OF THE DAY

- Floridians could carry guns in public without lice...

- HEALTH BENEFITS OF RIDING!

- 7 Simple Steps from a Cop on How to Fight Every Sp...

- AP Exclusive: Google tracks your movements, like i...

- BABE OF THE DAY

- CA - CLETS - Reports tally internal misuse of powe...

- USA - Stop and identify statutes

- USA - Supreme Court: Police need warrant to search...

- BABE OF THE DAY

- Boss Pays Off His Employee’s Mortgage So the Vietn...

- Meet the first female Marine assigned to fly the F...

- Bill giving servicemen and women largest pay raise...

- BABE OF THE DAY

- Bikers of America, The Phil and Bill Show, Return`s

- 16th Annual Iron-Workers Local-433 M/C Toy Run, 11...

- Loophole in law granting illegal immigrants driver...

- SAE J2825 Standard

- Could you be in California’s gang database? Bill w...

- his genius tool can save you money on Home Depot a...

- Preventing Police Abuse

- Why You Need A Video Camera On Your Motorcycle Or ...

- Gangs, Gangs, Gangs, Gangs

- BABE OF THE DAY

- US policing - Police violence, cliques, and secret...

- The Snitch’s Tale

- More info on the new Shared Gang Databases (AB 229...

- BABE OF THE DAY

- Enlightening police article on identifying and doc...

- .‘Sneak & peek’ warrants allow police to secretly ...

- If An Agent Knocks....Table of Contents

- Preventing Police Abuse Filing a Police Complaint ...

- Why Grandpa carries a gun

- Lane splitting by Motorcyclists is Legal in Califo...

- BABE OF THE DAY

- Bill giving servicemen and women largest pay raise...

- TOTALLY_KIDS 11/10/2019

- New police radars can 'see' inside homes

- A Little Education on the MC World

- What Are California’s Laws on Knives?

- CALIFORNIA - Here are the baseline knife laws in C...

- BABE OF THE DAY

- Trial by Written Declaration - California

- HESSIANS December 7 2919

- POLICE DEVIANCE & ETHICS

- Update on California Motorcycle Club Gang Validati...

- The Imaginary War Between MC’s And the Government

- Consolidated list of business establishments that ...

- BABE OF THE DAY

- BABE OF THE DAY

- Government Issues Orders to go after leadership of...

- USA - Rules for Resisting the Police State

- Can we record the police?

- Don’t Call Police. Ever.

- Terry stop...- In the United States, a Terry stop ...

- Preventing Police Abuse

- “THE BIKERS OF AMERICA, THE PHIL and BILL SHOW” 10...

- Breathalyzers not fully reliable: NYT

- In first, U.S. judge throws out cell phone 'stingr...

- The Getback Whip Issue Revisited.

- Adios Mexico

- Finally! You Can Qualify for a Concealed Carry Onl...

- CHECK OUT IF YOU MEET THE HELLS ANGELS MEMBERSHIP ...

- United States of America BILL OF RIGHTS

- Identifying and Documenting Gang Members

- The California Biker Black List

- California Criminal Record Expungement, Sealing, P...

-

▼

November

(112)

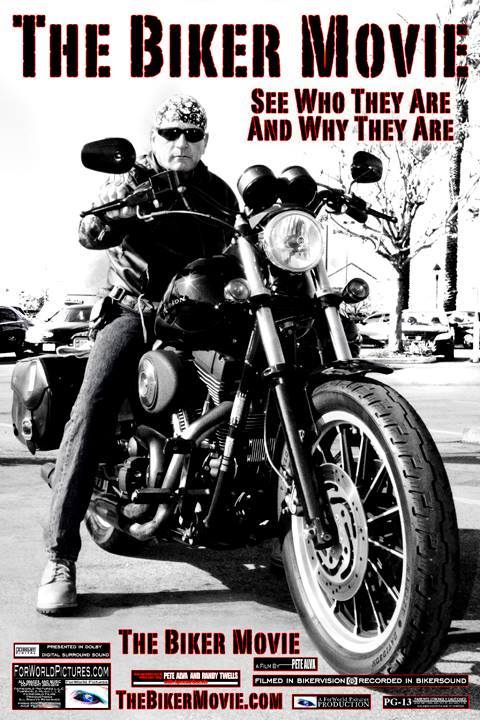

Bikers of America, Know Your Rights!... Brought to you by Phil and Bill

Philip, a.k.a Screwdriver, is a proud member of Bikers of Lesser Tolerance, and the Left Coast Rep

of B.A.D (Bikers Against Discrimination) along with Bill is a biker rights activist and also a B.A.D Rep, as well, owner of Kennedy's Custom Cycles